Working with Porcelain and Stoneware to Create High Fire Clay Bodies at High Temperatures

I work to create stoneware, white stoneware and porcelain clay bodies that are strong and resilient enough to survive being clinked around in the dish washer and dish water in everyday use. A major enemy of producing such durable utilitarian pottery is crazing, a fine system of cracks throughout the glazed surface of a fired pot.

Fired stoneware and porcelain pottery (high fire clay bodies) that exhibit crazing of the covering glaze are weak and fragile in comparison to high-fired pots where clay and glaze “fit” each other. Such pots can be 3 to 4 times stronger and therefore more durable than pots where the covering glaze is crazed. They are “sound,” and can exhibit a beautiful ring when lightly struck, as opposed to what may be a dead-sounding clunk of a fired pot where the covering glaze is crazed.

Heating Up

At the temperature I fire (cone 10/11, between 1286/ 1300C), stoneware and porcelain pots and their covering glazes are pyro-plastic, and may be near to the melting point. In this high temperature region of the firing, clay and glaze fit each other well, and an interface is created between glaze and the underlying clay body so there is no distinct separation between where the glaze ends and the clay body begins – the glaze is biting into the surface of the clay.

Cooling Down

As the kiln slowly cools, clay and glaze need to contract at similar rates to ensure a durable, “sound” fired result. If the glaze contracts at a higher rate than the underlying clay body, the glaze is put under tension; it is being pulled apart and crazing can occur.

Because the glaze is biting into the surface of the underlying clay, the body of the pot is put under tension as well, possibly weakening the fired result.

For my work as a potter of high-temperature utilitarian and decorative stoneware and porcelain, this all too familiar occurrence places the burden of responsibility on creating high fire clay bodies that display the ability to “fit” a wide range of high to low expansion (and contraction) glazes.

Exacting Standards

I work with 8 different requirements for the high-temperature clay bodies I create. These are excellence of workability, shrinkage kept relatively low, and absorption kept under 1% for stoneware and at very near zero percentage for porcelain.

Warping of the body must be kept to an absolute minimum and cracking eliminated. As a primarily porcelain potter, I gravitate toward smooth textures of the high fire clay bodies I produce.

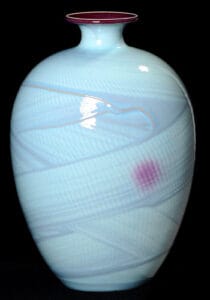

Fired color of the body is a highly personal choice among potters, and I’m drawn to a white fired result to attain the clarity of glaze color I seek. Lastly is glaze fit, the ability of a clay body to fit a wide range of high to low expansion glazes.

The process of creating such sound and durable stoneware and porcelain clay bodies for firing to cone 10/11 (1286 – 1300C) will be the subject of upcoming posts.